Gathering

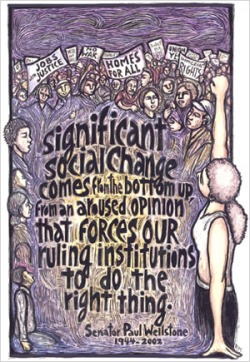

For the last month (maybe more, time has blurred) words have escaped me. I have found them this lazy afternoon, sitting in the whitewashed breezeway, surrounded by sleeping dogs. I am sheltered from the heat by stone latticework walls, creating patterns that jump and dance as the wind blows through the trees. The mango fruit are heavy on the branches now, dipping toward the earth as though surrendering themselves to harvest. New birds have appeared with the beginning of the monsoons, and I can hear them calling to one another in the breeze. The storms wake me at night, winds calling forth two months of rain and threatening to rip the tin from the rooftops, before the water comes, a wall of wet, plastering the tin back in place and beating it down with tiny fists. Lightning illuminates the corners of the bed, and in this place, I sometimes wonder if the sky is made of fire. At the beginning of June I travelled North, into the blanket of the Himalayas, blue mountains that unfold endlessly toward the sky. I went North to attend a farmers training, as well as to sit a meditation course at a retreat centre in the folds of the hills behind McLeod Ganj, home of the Tibetan community in exile and residence for His Holiness the Dalai Lama. En route (somewhere between the collision with the cow and the sleepy carnival that is the technological city of Hyderbad) our bus jumped over a pit in the road, lept toward the cliff edge and careened sideways, coming to rest with the back tire spinning squeakily over thin air. At first I called it a ‘bus accident’ but have since come to realize that it was more an ‘incident’ than ‘accident’, as the bus drivers and passengers alike nonchalantly clambered out, investigated the damage, built a ramp to lift the bus back onto the road, repositioned the 4 motorbikes that were hitched to the top of the bus, recounted passengers who were making the trip clasping to the rooftop and patiently reloaded the bus in an incredibly orderly fashion. The last month has been a lesson in mind and body, listening and patience. At first, it seemed as though all was the same. I walked, wandered, attended the farmers training and learned. The Tibetan community has committed to becoming fully organic in their food production, and hopes to be able to gather traditional Tibetan seeds that can be replanted in Indian soil. Homeless and displaced, the community seeks to find a way to dig deeper into India, to find themselves in this place of lowland heat and a cacophony of different languages. There place here is tenuous, and one monk told me that Tibetan seeds can help them to feel that they can build a Tibetan future within Indian soil, sowing earth for a shared future in the deep hopes of belonging and place. “It is important to scatter seeds” one Monk told me. “Seeds of all sort. Seeds of peace, seeds of hope. Seeds of awareness. Seeds of wheat, seeds of millet and ancient seeds of lentil. I would even like some seeds of chocolate!” Then the pain started. Radiating through my hip and back, I sat, I watched, I lay, I dreamed this pain, seeking the source and fighting off fear and frustration. I felt vulnerable and alone, wondering how I would manage in this fragile body, damaged by such a circumstantial ‘bump’ in the road. It was when I started to relax into this new sensation in my body that the teachers started to appear. Unexpected angels, arriving in the form of new and old friends, offered to help with my backpack, to find me food and to share bits of themselves to assist with my journey. Rendered helpless by the war raging between my shoulder blades and hips I watched, learned and discovered deep pools of gratitude for the gifts of Mother India. It was three weeks before I was able to make the return journey to Navdanya, and three more until I was able to come to a new understanding of purpose. I have always felt oriented around my body. I live, laugh, love and experience through my limbs, through movement and through the interaction of my body with the earth, soil and water. During my time in India I have been called outside of myself, my senses teased with smells, sights, tastes and the clear shock of new experiences piled one on top of another. I have learned that healing requires returning back inside, reclaiming the senses, and focusing my energy on the steadiness of breath, the stability of my core and the softness of being with gentleness. In all of this, I have found a new place, and a new sense of purpose outside of my physical body. I have shifted the focus of my work to that of the office, writing, organizing and helping with the planning of the systems that underlie the work that takes place in fields around the country. I found work waiting for me in the form of a food charter that one of the local communities is writing; documenting traditional seed, naming the community seed keepers, and recording the places and plants that fill the land that the community sits upon. The work is good, although not sweat filled labor of the type that I am in the habit of referring to as ‘a hard days work’. The work is gentle, and the work is sharp as a scythe, carving away at the old ways of thinking, the ways that distract the land from its purpose and fill it with untruths. I read as much as I can, trying to understand how we have allowed our systems of food, water and air to become so far removed from us. I try to understand how we can rebuild, reclaim and rewrite our futures so that like the Tibetan community, other communities can also find place and help to build land that will nurture and carry rather than harm. My work here at Navdanya has taken me into all of the caverns of life here; from the hands to the head, each infused with heart. In the midst of the language, the confusion of layers of conflict, acronyms of multinational corporations, international financial institutions and government policies that try to separate people from place and people from themselves, the old ways are reemerging. Communities plant, record and seek a new home, carved from the lands of change. We are coming home, and finding a new way into ourselves, our bodies and our communities. As the afternoon sun wanes, setting into the golden light that I will forever imagine infused with the ripeness of fresh split mangos and the strutting of white stilted egrets, I leave my perch in the whitewashed hall, and move to stand in the light. Taking off my shoes, I plant my toes and reach up, touching leaves with my outstretched fingertips. I too have been replanted during my time here. Small seeds of change have perched themselves, teetering lightly before settling into the moist soil of my consciousness. I have learned about patience, practice, humor and humility and the deep, abiding power of people and place. I have learned to shape chapatti, the delicious Indian flat bread, and to gently cajole spiders the size of my palm. Mostly I have learned about the power of the seed and the magic that can happen when a seed is planted and nourished. I will leave India in one week, country unfolding beneath me as I speed away. I am touched by this place, as I am touched by any place that I find myself. I can more clearly see the connections, the interactions which weave us tightly together across the great blue of this world. I can smell the sun warmed earth and taste the richness of harvest. Yes, seeds have been planted, and here they will grow Knee deep in soil:

Pausing this morning, knee deep in rich, most soil, I stand to stretch my back. I feel the coolness of the earth on my toes, and I wiggle them just a bit in pleasure. The sweat has run a river down my spine, and I am thankful for the way that it cools in the breeze. It is hardly seven in the morning, and yet, the sun up for hours, conversation bounces around me and the farm has been at work since dawn. Buoyed by the sugar and spice of a piping hot cup of chai (held gingerly in a tin cup between the fingers) and the promise of a few hours of (relative) cool before the stifling stillness of an unbearably hot afternoon, the work begins. Songs drift from around me, punctuated by the echoing ‘bang’ of a shotgun, fired high into the sky to keep the parrots, crows, pigeons, hawks and other hungry winged creatures from devouring the near-ripe crop of mangos. This soil is a testament to the healing power of the Earth. When Navdanya was started, almost thirty years ago, it immediately became clear that there was a need in India to demonstrate that organic farming could work. Vandana Shiva, the founder of Navdanya and her brother, Kuldip, found the perfect land for the project: a dessertafied, cracked, wizened landscape that had limped along cultivating a eucalyptus plantation for fifty hears before finally, even eucalyptus couldn’t be squeezed from the parched soil. There is a story that is told and retold here about how the local farmers laughed, and told Vandana and her brother that this was ‘wasted land’ ‘bad land’ and ‘broken earth’ not even worth the time that it would take them to drive here to look at it. Vandana, fierce woman that she is, stomped down the long road to where the farm now lays (or so the story goes), put both feet on the Earth and said, “here.” And here, Bija Vidyapeeth (the Seed University) was born; planted as a seed of stubbornness and dry, desperate hope. At first, the local farmers were proved right. Nothing could grow in the poisoned, overused soil that had been tainted by chemicals, plastics and years of monoculture cropping. There were no insects or animals to help with pollination, and each season more of the precious soil dried and blew into the hot winds that sweep from the foot of the Himalayas. It was a slow process, and a journey of great learning, as farmers who believed in the rejuvenating power of the Earth began to gather and learn from one another and the ancient traditional ways. In India, as in other places, the old ways are fading fast, replaced by colorful technology, fast ideas and plastic solutions. Elders were called, and the reclamation began, led first and foremost by the Grandmothers; keepers of the Earth and the original vessels of life. As Vandana told me the last time that I saw her: diversity is life, and uniformity is death. Without each precious part of the marvelous indivisible whole, the system begins to collapse. The seed is representative of the centre of this continuum. Containing the potential for life and the freedom to become, the seed offers food, nourishment and community for those who hold it. With the first harvest from the Earth at Bija Vidyapeeth a seed bank was created to honor and protect this potential. Within the seed bank, the best of the traditional seeds are harvested each year, and placed back into the bank for the following year. As Bija Vidyapeeth’s stock has grown, they have shared the seeds with the nearby communities, offering organic, traditional seed varieties that provide an option to the mountains of bags of yellow ‘quick grow’ seeds that flourish on almost any store shelf around the country. Instead of purchasing seeds that can not be harvested the following year (because they contain a ‘terminator gene’ that prohibits their propagation) and that require specific fertilizer (Monsanto brand, of course) to germinate, farmers become self reliant by harvesting, keeping and caring for their own traditional seed varieties. Grown in local soil, these seeds are miracles in responding to the challenges of the local climate. Millennium has shaped their response to drought and pests, and as only the strongest seeds are kept for the following year, each generation improves in strength and resilience. In return for the loan of the seed bank seeds, communities are asked to harvest their own seeds, and to offer the seeds back (at a rate of 125%) to the seed bank. This way the stock of precious life grows, and can be shared with ever expanding communities. Using this grassroots model to transform culture, the Earth, and the community life of rural India, Navdanya turns now to fight at the policy level against corporate interest. Vandana speaks tirelessly at the international level to raise awareness about food and water issues, while across the country (and the world) farmers are beginning to unite and to build community as they did in the old days, before the times of the mountains of yellow ‘quick grow’ bags. I recently received an email from a friend who is working in rural Kenya. She is living in a community in which almost 60 percent of the village is HIV positive, and she battles this stark reality each day. Food is scarce as Kenya has faced several years of serious drought, and as in many other countries of the world, Kenyan soil has been stripped by monoculture planting, pesticide use and a lack of crop rotation. People are hungry, and so when huge, white trucks with tinted windows thundered into town, people arrived in droves to see what strangeness they brought. In the heartbreaking tale of world globalization, it was Monsanto who arrived in this small, rural village, deep in the heart of Kenya. Company representatives carried food, Western cereals, bags of cookies and protein bars. They offered the food to the hungry villagers along with a small, yellow bag, with the words ‘quick grow’ written on the paper. Buy our seeds, they told the villagers. This will solve all of your problems. Hunger-glazed, the people looked back at the strangers, awed by the display of wealth and food; and the cycle begins again, even here. In the fields of Bija Vidyapeeth, I stand next to Didi (older sister), a wizened elder who shines with laughter and years used well. She gestures to me, and I turn to her, and marvel at the heat glimmering around her, making her seem as though she is a part of a miraculous mirage that has drawn her from the Earth itself. She throws her head back in laughter and squints her eyes at me, pulling up her sari and showing me her legs, caked in soil to the thigh. She shouts at me in Hindi, laughing harder as it becomes clear that I do not understand what she is telling me. “I have become the Earth”, my friend Suneal translates, laughing along with Didi. I laugh too, and it surprises me, coming so fast that I have to sit down to catch my breath. “I am the Earth too!” I shout. “Or maybe,” I giggle “it is the Earth that is us?” And the morning leaves Didi and I there, knee deep in soil, bent over in laughter, and buried in rich, regenerated Earth. And the Truth waits: As old as the hills

Taking a moment in the sweltering heat of the midday afternoon to reflect. It is May 25th today (I have to look at the calendar on the computer to know the date). I have completely lost track of time and reality feels sometimes to be a distant haze beyond the heat, new language and shifts in body, place and food. I remember before I travelled the first time I thought that culture shock was something that would feel ‘different’ – perhaps like an illness, or something tangible and understandable. I recognize today that culture shock can be a slow moving haze, covering me in overwhelm and confusion. When I am not tired, newness is exciting, adventurous, a learning opportunity. Today I am hot, tired and overwhelmed, and I desperately wish I could have something cold to drink. At lunch time one of the men on the farm asked me to ring the lunch bell to beckon the other workers to their meal. It took us five minutes of hand gestures, laughing, sighing and finally him rolling his eyes for me to understand what he wanted. Thank the universe for his patience! This afternoon I hide on the quiet side of the building, out of the sun and away from eyes. I revel in the moment to myself – fully expecting the space to be shattered by any manner of the unexpected magic that permeates India. I am covered in cuts, bites and bruises, and I think the day spent weeding in the sweltering heat yesterday has finally taken its toll. I am almost out of rehydration salts – and although I am aware of the complaints that I am submitting you to – I am tired of rice and dahl three meals a day! How conditioned I am to choice – to getting what I want, to being able to communicate when and how I would like to. One part of my mind fights with the mosquito bites, the cuts, the bruises and another part of my mind looks down at my body and celebrates its labor in the hot sun and its yield of food to nourish myself and others. How grateful I am for the choice that I have had in my life, and the preciousness of each and every warm, wonderful clean-water shower! I am reading An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth by M. K Gandhi. It is fitting to read his original words in this place which has been based on his life and work. He writes of simple things, asking, ‘what is truth’ and ‘what is humanity’, and I love his words. Today I wrote in large letters in bold ink down my arm, “I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and non-violence are as ancient as the hills”. These words offer me the reality of life and body, and remind me of gratitude and appreciation for the depth of those who have gone before. Yesterday I met with Dr. Vandana Shiva, founder of Navdanya, and imminent Indian scholar and activist. I remember the first time I saw her, a tiny head above thousands of people at the World Trade Organization protests in Seattle in November of 1999. It was a moment of birth for me, perhaps even one in which I discovered another way of being and the spark of true critical thought. It was a moment when worlds came together, and I began to understand how the global could be connected to the local and the local to the global. Vandana is a robust woman, who speaks in a lilt of rolling ‘rrrr’s’ in clear English. Her eyes dart around the room as she speaks to me, and I think that she may be carrying on 4 or 5 different conversations, only one of them with me. Another has to do with her blackberry, into which she is loudly declaring that she “must be in Frankfurt, no matter what, May 19th”. For a moment she fixes me with her stare, and nods her head. “Yes?” I tell her that I want to take the work that Navdanya is doing back to Canada, by preparing writing and presentations that I can offer back to Canadian communities. When I pause for breath, she returns to a conversation she is having with a man who stands behind her; “just sign the papers, Jeeka, just sign them!” she shouts. My interview over, I emerge into the sunlight dazed. A brilliant mind, a busy woman. I am confronted with the reality that what I can offer Navdanya is really very small in relation to the work that is needed, and Dr. Shiva recognizes this. This time requires humility and patience. Perhaps Navdanya’s true gift to me will be the cultivation of my own seed of practice, the seed of the work that I can take from this place. In many ways, I am lost in India. It is not my place, my culture or my language. When in India I must hold firmly to my suitcase packed with laughter, patience, humility, digestive enzymes and a healthy dose of expecting the unexpected. In Canada, I know my way around. I can express, reach audiences, speak and act in a way that opens up (at least somewhat) expected avenues of change. In the distance I begin to understand the value of home, and of the change that I can affect in my own community. International Development has become not about working in another place, or being in another culture. It has become about linking the local to the global, and bringing the global to the local. We live in an interconnected world of self and other, and it is a wild, wonderful magical place, with knowledge as old as the hills. Roar of the Earth

The last few days have been a whirlwind of sights and colors. Settling into Navdanya has been like a dream, one misty morning followed by scorching afternoon, followed by star filled evening after another. The sounds of Hindi are becoming more familiar to my ears and I have learned the names of most of the community members here. There is Ganga in the kitchen, who sings while he cooks, and Jeet, the man who has come from deep in the Himalyas to work with Navdanya. Leaving behind his family as so many men from this area must do to send money home, he tells me that he is so grateful to have this work that pays him well enough that he does not have to go into the military where he may be killed in the ongoing conflict that holds Kashmir in chaos. As I feel the shifting of the early morning breezes on my face, I can hear the calling of the cow herders, chasing wayward cattle, intent on greenery rather than roadside garbage. There is the ever rumbling clackity-clack of the busses (shocks long flattened by years on the road) shaking their way down the main road, the swaying of white butterflies and the still sweat of the promise of heat. Last week I journeyed with a group of interns into nearby Dehradun, the capital of Uttaranchal, and a dusty sprawling metropolis that seems to hold 10 degrees in its concrete. Perched in the back of the clackity-clacking bus on a swaying tank filled with gas I am passed a small child to hold, and I clutch her to me, although I know that she will not keep me from bouncing out of the open bus door at the next bump in the road. After a dusty day of shopping (and the most incredible air conditioned supermarket stocked floor to ceiling with Belgian chocolates) we visit the nearby community of Tibetans in exile. A golden Buddha stands serenely in the centre of the monastery, which seems to be the hub in the spokes of windy Tibetan streets. The colors are brighter here, and the sky is filled with rope upon rope of prayer flags, whipping mantra across the entire valley. My work at Navdanya is settling into a routine. I have been helping the office with their monthly reporting (which they are three months behind in) and I am working my way through creating a form that can be used to report to funders. In between power outages (when everyone yells at me simultaneously in a variety of languages, “SAVE, SAAAAVVVE!” before the computer screen goes black for an unknown length of time) I walk to the fields and practice what is known in Hindi as the ‘essence of humility’ or labor in the sun. There are always ways to help: the spearmint patch needs weeding or the cows have eaten the cabbage and it needs to be replanted. Over it all is the endless shifting of rice and lentil grains, and the discovery of hundreds of tiny rocks, insects and pieces of dung in between the precious bits of food. Navdanya exists in response to the corporate control of food systems. It links farmers around India and across the world in the fight for that which sustains each human being on this planet. Corporations such a Monsanto are urging India (and other countries around the world including Canada) under the World Trade Organization (WTO)’s TRIPS (Treaty of Intellectual Property Acts) to patent all of India’s traditional seed sources. Once patented, the seed becomes the private property of the corporation that has patented it, and farmers can be sued for property violation if they grow the patented seed without purchasing a license. Once patented, seeds can be genetically modified until they become ‘terminator seeds’, seeds that do not regenerate on their own but instead must be ‘initiated’ by a chemical process. These seeds can not be saved, and must be bought each planting season. In response to the far reaching consequences of this inhuman practice, over 17,000 farmers have committed suicide in India over the last 10 years. No longer able to meet farm debt payments, or support their families, death seems to be the only option. Navdanya is in the centre of the fight against this tragedy in India. Linking farmers around the world, Navdanya supports farmer education and works for policy change in India and beyond. They have already successfully overturned the patents on Indian basmati rice, neem products and on a traditional variety of eggplant – however, the fight is ongoing, and corporate capitalism weighs heavily on the side of genetic modifications. The beauty of this place is saturated in this context, and with the deafening roar of the earth. Each plant seems precious, the earth a vessel of the sacredness of life. It brings me to tears to think of the cruelty that humans have toward others on this earth. How can it be that we live in a world where some can take away the right of so many to have access to water and food? How can it be that profit is more important than feeding a child? How can it be that the lies of genetic altercations of food (that it produces more food or that it helps crops to be resistant to disease) can be told again and again and believed? It is a struggle for my mind to find balance in this reality. In the world as it is today, it becomes a radical act of resistance and creativity to sit on a burlap sack, somewhere far in the Indian countryside sorting each tiny grain of rice into small piles. It becomes revolutionary to hoe in the garden, and to transplant one tiny calendula plant, which will later be harvested and made into a balm for cuts and bruises. A part of me wants to be in the streets, or at the doors of the government – telling someone, anyone, who will listen what an atrocity this mess is. Another part of me is content in being patient, and remembering the revolution of the seed as I sit in the shade and run the dusty grains of rice through my fingers. “I am a farmer”, my new friend Biju told me. “I am simple, and I am honest. This is enough to make the world change." Navdanya:

For the first time, I can see the mountains. In Rishikesh, although the city is built into the sides of the hills, the mountains seem distant in the fog, heat and pollution. Only in the early morning and evening can the mountain tops be seen at all, and while there is a sense of them all around, they are like ghosts looming somewhere far overhead, felt rather than seen. Here at Navdanya, nestled at the base of the Himalayas, outside of the city of Dehradun, the mountains bookmark the sky, greeting the great sprawling Indian plains. Arriving to Navdanya, dusty, exhausted and overwhelmed by days of travel, sickness and the heat which is so new to my body, I notice for the first time the sounds of birds. Birds of more kinds than I can count, mango trees swaying in the breeze and trees reaching their leaves toward the sky. In Rishikesh the trees have all dropped their leaves in the dry season, and the green is like a breath of clean air for my vision. I am taken to my room – in a long hallway of rooms facing out toward the farm. The buildings are made of mud, rich in hand mixed painted color. The man who shows me to the room offers me great kindness when he takes me by the shoulders and tells me that I am welcome here. He tells me that I am home, and that I can know that this is true. Cultural appropriateness aside, I hug him, and then immediately leap back, embarrassed. He laughs, and tells me to sleep. I lay on the porch and rest in the breeze. Lazily opening my eyes at an unknown ‘woosh’ sound, I am surprised to see that the mango forest is suddenly covered in beautiful white birds. Strutting slowly, they watch the ground for bugs before snaking their heads out to reach for their food. If there is one thing I have learned during my time in India it is this: things are not as expected – and Navdanya is no exception. It turns out that I had not been expected by the farm staff. Somehow there was no communication between the offices in New Delhi and the Farm, so there is no set project ready for me here (although I hear this is often the case with the Delhi interns also). Speaking to the other interns who are here they share stories of the moment they discovered that their internships were truly ‘up to them’ and the projects that have emerged from this freedom. The person that I have been communicating with by email from Canada (my ‘supervisor’) left the organization last week without a word, so I was able to meet with another person here this morning who will be able to serve as my official ‘supervisor’. His first words of supervision? “Find something you like, and do it!” Ok! Here I go! The farm is at work all of the time, and yet the work itself is more a part of life than something separate. It is the work of creating food, sharing food, sorting out community life, cleaning seed, meeting with the farmers, sweeping the floors. It is a life of imminence and magnificent presence. This morning I sat for hours with a group of women sorting tiny rocks from lentil seeds, listening to the lilt of Hindi and watching the rain pour down. My busy mind struggles with the imminence of life here. I have been hurrying for years it feels, rushing to complete one known for another unknown. Time has sped up, leaving me feeling oftentimes lost in the confusion of fast-paced hustle. Could it be that Navdanya will offer the chance to learn in a pace that is so different from that which I usually push myself toward? That it could offer me the freedom to explore to the depth that I want to go? As I write this I can hear the sunset call to prayers coming from the nearby community. There is an owl hooting in a nearby tree, and the sky is filled with the flush of pigeons. I have crushed spearmint leaves on my hands from where I spent a blissful hour weeding this afternoon, and the sky is shifting to a beautiful shade of purple. Could all of the last week have happened in the same India? The crowded, garbage filled streets, the poverty, the devotion along the banks of the Ganges in Rishikesh? This space of mangos, earth and place? I have been blessed with the appearance of so many unexpected angels on this journey. In arriving at Navdanya I feel I have met another. I will spend this week defining the work that I will do – and working each day with a different part of the farm. There is a man here who is doing a photography project for a book on Navdanya, and he will be travelling to some of the farms across India that are a part of the Navdanya network of Organic farm workers, and documenting the stories of the farmers that Navdanya works with. Perhaps I will have the chance to join him. Only tomorrow will tell. I met a woman in the library tonight who tells me, “it is all connected. Here, there, everywhere. Somehow everything is connected at Navdanya too. I just have to understand how.” I feel the same way. I wait: Blue lightning arcing over the banks of the Ganges

There is unexpected magic permeating each of the movements that I make here on the red Indian earth. I have prepared for this trip for moths, writing funding grants, learning all that I can about India and the work that I will be doing with Navdanya, a grassroots organization working on preserving cultural and biological diversity across India. The work is a final graduation requirement for me, in completion of the Masters of Social Work degree that I have been navigating my way through at the University of Calgary. Specializing in International and Community Development, this degree has offered me the chance to link issues in Canada with issues around the world, and to seek insights of change and potential. I believe in life, in hope and in the inevitability of a better world, and it is this passion that has driven me this far, awakening unexpected turns in life and finally, allowing all else to temporarily drop away and leaving the dusty roads of India here; directly on the horizon before me. Waylaid en route to the community of Dehradun (the closest town to Navdanya) by an unexpected festival, a once every 12 year event that brings together millions of spiritual seekers (Sadhu’s) from across India, I find myself remaining on the train, drawn by some irresistible urge to pay my respects to my spiritual home. A bus ride, traffic jam, adventure with a cow and a haphazard trip on the back of a bicycle later, I stand in awe at the banks of the Ganges river, deep in the soul of Rishikesh. There is a heat here like nothing else I have experienced, and the river seems to breathe with it, waving in the heat as though it is alive and the lungs of this place. By sunset, the heat sends arcs of electricity shooting across the sky, as though the temperature is something physical, alive and powerful. Making my way to the banks of the river for the fire purification ritual of Aarti, the rain begins to fall and each splatter offers a tiny oasis of cool against my parched skin. I let myself become a part of the colorful crowds, swaying this way and that as people remove their shoes and find a corner to sit. An old woman in a sari the color of sunrise grasps my hand and pulls me down beside her, gesturing for me to share the burlap sack that she is sitting on. Looking out over the river and feeling the push and pull of people arriving for prayer I wonder what force it is that has brought me here, and how it is that I have come to this place. There is a large statue of Shiva at the banks of the river and water shoots from his head, just as it does (so they say) at the sacred root of the Ganges deep, deep in the cool Himalayas. A song begins to build and the pulse of it is taken by the crowd. People all around me are sighing, singing in the rain, blue lightning arcing over the banks of the Ganges. There is a woman dancing on the marble at the foot of Shiva, her eyes closed, face tilted to the rain which has began to pour down in earnest now. I can see the water washing her face, and taking the red stain of earth from her feet. She stands in a pool of red, as though her blood is being washed away, leaving her face intent, bliss filled and heart open. Her sari is plastered to her chest, and she moves to a rhythm that is her own, describing her own secret, sacred dance to the universe. With a whoosh (and the crack of deafening thunder) the Aarti lamp is lit, and I am pressed back by the crowd which swoons toward the purity. I stand and let my body be carried toward the light, offering my hands toward the heat before turning to wash myself in the sacred Ganges. It is said in India that when one is cleansed in the Ganges it is possible to begin life again, to open purity in spirit and body. As I kneel and touch the water I feel like the earth, water, fire and air have opened at once in a marvelous display of magnificence. The sky cracks open and for an instant, all is light, before it is dark again and I am deafened by a roar of thunder that feels like the Gods of the clouds have jumped directly above my head. I sit on the cold earth, bodies black in the darkness pressing all around me and marvel at this moment. In the midst of the challenge of New Delhi, the intensity of unbelievable poverty, the crush of mind numbing oppression, the complications of global politics and phrases like the “Global North” and the “Global South”, there remains this place and this instant, standing still for thousands of years to greet each sunset with fire by the banks of the Ganges. I press my hands to my ears, wondering how it is possible that the world can hold so much, and I, such a tiny speck, guided this way and that. I hold the promise of this moment, the gift from the feet of Shiva close to my heart, and wait for mother India to unfold. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed